five films to watch when you want to change your job

If you're at this point and you've decided to try something new, we've put together a list of movies that will help you on your way.

Some people are very lucky: they go to work and love their jobs, or at the very least, they go to work and feel grateful because their jobs give them the financial freedom to buy things like pizza and towels. Gratitude, like love, can make you forgive a lot of things; so sometimes, even when your job isn't amazing or personally fulfilling, or doesn't make you feel like you have discovered the one reason why you have been put on this big brown earth, gratitude can make you feel content.

Sometimes it gets to the point, though, when you either: 1. Can't take it anymore (I've been there, I hear you); or 2. Decide to take the plunge and do something that you've always wanted to do (I haven't made it there yet, but if you have, or you are right now, I wish you all the luck in the world). Change, when it reaches this point, is something that moves in swiftly like a storm, and demands that you pay attention to it if you ever want to feel like yourself again, or if you want to feel like yourself for the very first time.

If you're at this point and you've decided to try something new, we've put together a list of movies that will help you on your way. A new job might be right around the corner, or you might find new inspiration in what you already do. Catch Me If You Can

Catch Me If You Can

Spielberg's true story of a teenage pilot-doctor-lawyer con man shines most brightly as a fun, seemingly risk-free run-around. How much danger could you really be in if you're being chased by Tom Hanks? For a kid with a fistful of forged Pan-Am cheques the world is as light and frothy as whipped cream. Yet, fittingly, the fun and bubbly parts of Spielberg's film disguise its haunting vision of work as nothing but a cutthroat shortcut to wealth and self-enrichment. If you're only doing something for the money – even if you're qualified – then aren't you just pretending too?

It's a Wonderful Life

It's a Wonderful Life was released in 1946, immediately in the wake of World War Two. The movie was a stark critical and commercial failure for writer and director Frank Capra, who was derided for his apparent sentimentality and the film's apparent cheese-heartedness. What was missed then, but has thankfully been discovered since, is the movie's extraordinary depiction of what it can mean to wish for a different life. Perhaps more powerfully than any other story – filmed or otherwise – it reminds us of what we might stand to lose if we believe that the life we have now is inadequate to who we think we could or should be. Life, even when it's not the life we planned for, can still be, in many ways, wonderful.

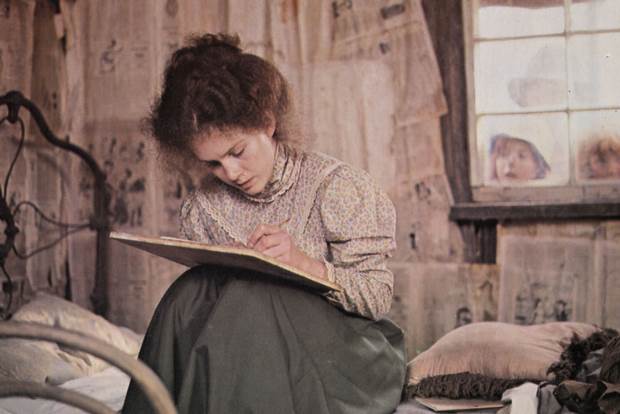

My Brilliant Career

For a short while, during the 1970s, Australia was producing some of the best and most exciting movies in the world. My Brilliant Career, directed by Gillian Armstrong, was one of the high points of the films released during the Australian New Wave, which included Picnic at Hanging Rock, The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith and The Getting of Wisdom. My Brilliant Career resonated with its cultural moment – with the changes won by second-wave feminism during the 1970s – but also showed how Australia's 19th century history is linked with the massive transformation of the world that feminism wrought. Judy Davis' frustrated teenage writer Sybylla aspires to set out from the straits of rural life to become a writer. She is warned that "loneliness is a terrible price to pay for independence", but insists on committing herself to writing and finding out, in her words, "what is wrong with the world, and with me". Work, in this way, can be a path both to self discovery and a way of making sense of things that are bigger than ourselves.

Bill Cunningham New York

This movie is really, really fascinating, and (appropriately for its subject) a modest but strongly moving picture of the Boston-born Bill Cunningham, who photographed the unruly sartorial life of New York City's streets, publishing a selection of his material for the New York Times. What is most important to know about Cunningham is that despite spending his life photographing clothes and the people who wear them – and, therefore, mixing with the brightest and wealthiest in society and fashion – he refused anything more than the most basic of payments: only enough for somewhere to eat, sleep and store his photographs. He would not be held hostage to high fashion or anyone. "If you don't take money," he says in the film, "they can't tell you what to do! That's the key to the whole thing!" In being beholden to no one else, in having to satisfy no one's vision but his own, he was self-employed in the purest and truest sense of the word.

The Social Network

When David Fincher's biopic of Facebook co-founder Mark Zuckerberg came out, a lot of the talk focused on whether or not it was "accurate", whether what it showed us "really happened", why Facebook was "really invented", what Mark Zuckerberg is "really like" and so on. This is all a bit strange if you consider for a moment that the opening scene – in which the fictional Zuckerberg is dumped by his girlfriend – completely breaks from the basic, established historical fact that, well before the development of Facebook, Zuckerberg had been in a romantic relationship with Priscilla Chan, to whom he is now married. So it seems clear that Fincher and scriptwriter Aaron Sorkin are probably less interested in the historical facts of Facebook's invention and more in how the building of the social network giant might be the vehicle for a more universal drama. The opening conversation lays all of this out, framing the movie through a discussion of genius, education, and the wish to "stand out". As with the compelling hacking sequence and the later scene of Zuckerberg walking out of a lecture – because he can master the content without effort – the opening scene clearly paints him as some kind of genius but one lacking a crucial sense of proportion between individuality and sociability. He's the smartest guy in the room – that's for sure. But the real question is: despite the inevitability of his career success and his incredible skills at using and understanding technology, which is meant to bring people closer together, is he himself properly in touch with the human world?

.jpg&q=80&h=682&w=863&c=1&s=1)

.jpg&q=80&w=316&c=1&s=1)

.jpg&q=80&w=316&c=1&s=1)