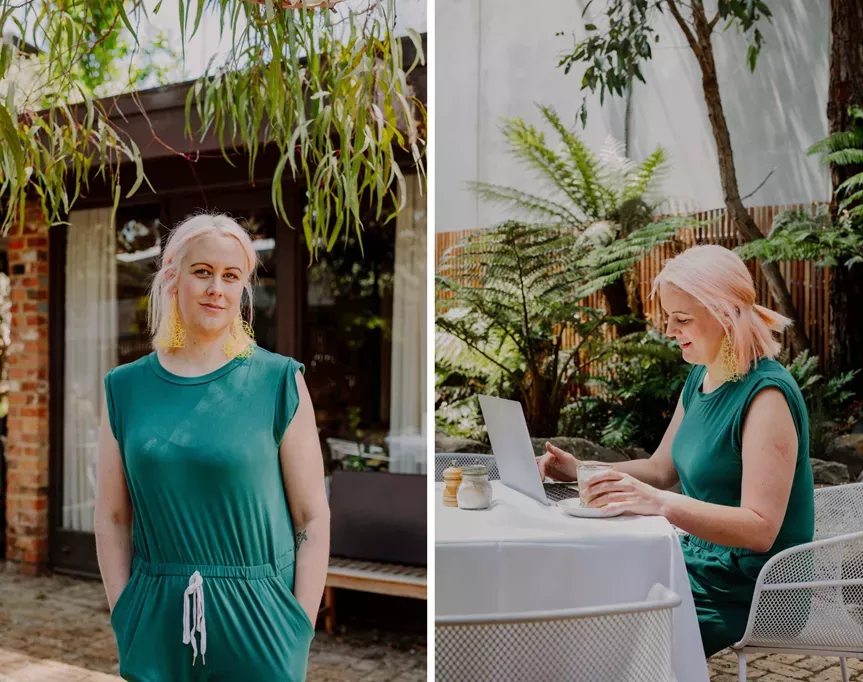

escaping the trap of busyness

Author Madeleine Dore explores busyness, burnout and rest.

If we spent a day collecting the answers we hear to the question "How are you?", we wouldn’t be wrong in thinking 'busy' has become synonymous with ‘good’. We both project and presume busyness with the phrases "I’m so busy", or "I know you’re so busy". Instead of sharing what’s novel, what we might need, or what’s concerning us, we use ‘busy’ as a stand-in for what’s really going on in our daily and inner lives.

'BUSY' AND 'PRODUCTIVE' IS NOT THE SAME AS 'WORTHWHILE'

When we perceive that we don’t measure up to our own expectations of busy, we experience productivity guilt. Everyone else appears to be busy, we think, and here I am in the midst of my day, not quite busy enough, but not quite able to step into the room of rest while the pressure to be busy follows me around. At times, busyness is unavoidable. Other times, busyness can be tied to coping with the day – during challenging times, some people take on more simply as a way of keeping moving. Sometimes, we embrace busyness. Work, multiple creative projects and a full social calendar can give shape to a day. Or perhaps it’s simply our natural frequency to be busy, and to dampen it would mean dampening ourselves. But there is a distinct difference between the busy that is unavoidable, a comforting buffer or for our own momentum, and the needless busying that can perpetuate productivity guilt. That is, the busyness we wear as a badge of honour. For many in privileged circumstances, this busyness for its own sake is a choice, yet we rush around as if we have no say in the matter.

It can be difficult to unwind from the trappings of a busy world – especially if we’re contending with financial precarity, or have dependants, or are focusing on a long-term goal. But for those of us who lament being busy and could find ways to be less so, why don’t we? Surely we don’t want to be so busy that we don’t have the time to connect with people. Surely we don’t wish to be so busy that we don’t enjoy our lives. Surely we don’t really think busy is good – we just needed the permission from each other to be something else. After all, busy is not the same as productive, and productive is not the same as worthwhile.

THE ROAD TO BURNOUT

Busyness can be a prelude to burnout – the deflating and depleting condition that’s hard to define, but is currently defining generations. At times, the number of things we think we should be doing – in our days and to save the world – feels impossible. Tasks that should take only a few minutes can stretch into hours, while other work mounts up. Life becomes a ceaseless frenzy in which we always feel like we should be doing more just to keep up with everybody else – who all seem to be coping fine. We rarely glimpse the truth: that others are flailing too.

Just as the sources of burnout are many – an infectious pressure to be busy, for instance, or the precarious or uncertain nature of work, or troubling external events and circumstances – so are our experiences of it. The two-phase description by the writer Honor Eastly has long stuck with me: crispy and burned out. The crispy phase precedes burnout, and occurs when Honor is stretching herself but still enjoying the process. The second phase comes when movement grinds to a halt – you feel stifled and burned. This two-phase framing for burnout helped me recognise burnout amnesia in myself – the tendency to forget that if I keep running when I’m on fire, I might get burned. It’s helped me recognise my own signals of crispiness before I land all the way in phase two: waking up at three in the morning worrying about a crowded to-do list, an intolerance of mess and noise, feeling alone, despondency, ruminating on what other people think. When I spot these signals, I can turn to the things that might help me cool off – asking others for help, taking deep breaths, exercising, resting, switching on an auto-email responder.

While this approach can be helpful to spot the warning signs, burnout can still blindside us. This might stem from the narrow definition of what we consider to be ‘work’. Raising children, for example, isn’t often considered ‘real work’, as it should be. Even creative pursuits are denigrated in this way. This perpetuates our feeling of not doing enough, because what we do supposedly doesn’t count. If we have internalised the idea that we should be busy all the time, or see no escape from the busyness of daily life, how do we find any reprieve from the consequent burnout? It’s tempting to turn to a productivity hack or a new system to organise our lives, but these are like bandaids if we don’t address our collective resistance to what we need most: rest.

REST IS NOT A MORAL FAILING

When our culture is pushing us into a spiral of busyness, rest may be the only thing that helps keep us intact. Rest shouldn’t be for the sole purpose of making us more productive – it has value in and of itself. It reminds us that we are not machines, but human beings. When we embrace rest or take what is within reach for us – be it a guilt-free nap or a sabbatical – we can demonstrate the value to others, too.

Part of the challenge of working less is that we’re entrenched in a system that demands more and more, but it might also be true that we’ve been taught to resist rest. Even the weekend has fallen victim to our need to avoid rest – through devoting time to a side hustle, or dashing between social catch-ups, the hours hurtle by until we greet the ‘Sunday scaries’ and wonder where our chance to rest went. Having a work-free weekend – or even taking a break – has almost become a lost art. Even when we know we need rest and have the privilege to take it, it can be difficult to convince ourselves to do nothing – without also having a side of self-flagellation.

Viewing rest as self-replenishing rather than selfish might help ease the guilt or shame some of us feel for taking a break, and instead help us to see that it’s part of the rhythm of the day. It also shifts the frame so we see the inherent value of rest – we need it to restore and replenish, but also to rethink. The trap we can find ourselves in is that we are too busy to rest, and so we don’t have the time to rethink our circumstances and come up with another way to be. Rest might be the key to releasing us from the busyness trap, because it’s the very thing that can help us see we’re in it.

Giving yourself permission to rest in the way you need it can be the very thing that allows you to discover more opportunities to shape your day, rather than having busyness shape it for you. Taking things slow and slothful can help us survive. So find the beauty in the break. Enjoy that moment of boredom. Be OK with what is left undone. Allow yourself to rest, pause, ponder, daydream, laze, do nothing. Listen, watch and reflect, and embrace the possibilities of not being busy.

This is an edited extract from 'I Didn’t Do The Thing Today' by Madeleine Dore. Murdoch Books RRP $32.99.

This rad article was originally posted on March 8th, 2022.

.jpg&q=80&h=682&w=863&c=1&s=1)

.jpg&q=80&w=316&c=1&s=1)

.jpg&q=80&w=316&c=1&s=1)