the history of orthodontics

When did we all become so obsessed with perfect teeth?

Of all the parts of the human anatomy, teeth definitely require the most maintenance. They’re the one bit of us that seems carelessly designed. God’s tedious mistake. If you leave teeth alone to do their thing, they will probably corrode, fall out, decay, grow in weird directions, become infectious and potentially even kill you. Kind of makes you wonder how the human race has survived with 32 little time bombs of pulp, dentin, enamel and cementum inside our heads.

The funny thing is, teeth are sort of an example of evolution going backwards. The average caveman probably had better natural teeth than you. Survey data has found that roughly one fifth of the US population has significant ‘malocclusion’ (literal translation: bad bite). Today, nearly half of all kids require some sort of orthodontic intervention to stop their teeth hulking and growing upside down. This usually takes the form of braces (the natural enemy of the apple), which drag the teeth painfully back into alignment.

But cavemen obviously had no dentists. So what gives? Surely Neanderthal fossils must be an orthodontic freak show, right? Well, not quite. As evolutionary biologist Daniel Lieberman noted in his book, The Story of the Human Body, “The museum I work in has thousands of ancient skulls. Most of the ones from the last few hundred years are a dentist’s nightmare: they’re filled with cavities and infections, the teeth are crowded into the jaw, and one quarter of them are impacted. In contrast, most of the hunter-gatherers had nearly perfect dental health.”

Yep, most hunter-gatherer fossils reveal beautifully spaced, even, well-aligned, Hollywood teeth. They probably smelled pretty bad, but from an orthodontic point of view, Neanderthals were A+ patients. Turns out the size of the human jaw has been shrinking consistently over the last 3.3 million years, ever since we started farming and stopped chewing big hunks of undercooked mammoth. We basically have Stone Age genes in a Space Age world – a world of cooked foods, soft mush, small mouthfuls and sugary drinks – and the result is smaller jaws, crowded teeth and crooked smiles.

But as our diets changed, so did our approach to dental care. You might think dentistry is a relatively modern science, but archaeologists have found 14,000-year-old infected molars that were cleaned with flint tools. In Pakistan, a 9,000-year-old tooth showed evidence of been drilled for decay (ouch). They’ve even found a 6,500-year-old beeswax filling in Slovenia. Three thousand years ago, ancient Egyptians and Babylonians used (non-dentist-approved) twigs and sticks to remove plaque from their teeth. It was around this time that white teeth started becoming a sign of youth and general hotness.

Modern dentistry technically began with French physician Pierre Fauchard in the 1700s. He was the first guy to realise that tooth decay was caused by sugar, rather than magical ‘tooth worms’ or an imbalance in your body’s humours (aka blood, yellow bile, black bile and phlegm).

Fauchard fashioned the first orthodontic bandeau, a metallic band that expanded a patient’s dental arch, but he didn’t really invent orthodontics. The ancient Egyptians got there first. Archaeologists have found mummies with metal posts on their teeth, tied with catgut, kind of like a modern retainer. The Romans threaded gold wire through people’s teeth to straighten them out, and the Etruscans even used primitive mouthguard in the afterlife.

So why are we so obsessed with straight teeth? It’s mostly a cultural thing. Specifically, a Western cultural thing. Crooked teeth do increase your chances of gum disease, decay, bad breath, tension headaches and infection, but that’s usually only for severe cases. A wonky incisor or slight overbite usually isn’t a major issue. (Disclaimer: please get your dental advice from a health professional, not an arty-crafty magazine.)

The West has been keen on symmetrical teeth since at least the 1700s. Thomas Berdmore, personal dentist to England’s King George III, wrote that straight teeth “give a healthy juvenile air to the countenance, improve the tone of the voice, help mastication and preserve the opposite teeth from growing prominent.”

By the 1800s, symmetrical, clean teeth had become a class symbol, but also a weird sign of interior moral virtue. Painters would often use an open mouth and wonky teeth as a metaphor for obesity, greed or corruption. As author Angus Trumble writes in A Brief History of the Smile, “Most teeth and open mouths in art belonged to dirty old men, misers, drunks, whores, gypsies and – all together now – tax collectors.”

In America, as 20th-century dentistry conquered tooth decay with advancements in fluoride and microbiology, an open smile became more normal. People suddenly wanted to show off their teeth. Product advertising began featuring toothy, corn-fed American children with blindingly white smiles; a sign that the smiler was wealthy, healthy and clued in to modern science. The Kennedys had pearly whites you could practically read by. In Australia today, dentists estimate that the demand for veneers and teeth whitening has doubled in recent years.

But not all cultures value straight teeth the same way. In Japan, for example, some women actually pay to have their teeth disarranged. Think reverse braces. It’s known as the ‘yaeba’ or ‘double-tooth’ look, and some young Japanese find it attractive. Michelle Phan, a Vietnamese-American beauty blogger, summed it up this way: “In Japan, crooked teeth are actually endearing, and it shows that a girl is not perfect. Men find that more approachable.”

We can see a similar thing in mainstream Western culture, with the recent trend towards tooth gaps (also known as diastema, and usually caused by delayed baby teeth). Lauren Hutton popularised the look in the 1970s, and models like Lara Stone and Georgia Jagger brought it back, to the point where dentists reported patients wanting to widen their tooth gaps, or reverse previous closure work. Imperfect is, apparently, the new perfection.

And what about the British smile stereotype? Do Brits really have bad teeth? Eh, not so much. As you might have guessed, this is just a lazy cliché. On pure oral health, Britain actually scores better than the Hollywood-smile-obsessed US. According to OECD figures, the average number of missing or filled teeth for a child in the UK is around 0.7. In America, that number is 1.3. (And in Australia it’s 2.5 – yikes!) Take that, Big Book of British Smiles.

So yes, not all teeth are created equal, but they can become more equal with expensive and painful reconstructive orthodontic work. And that’s probably something to smile about.

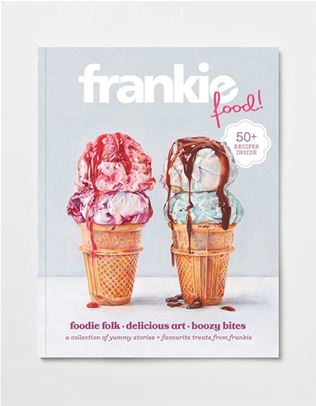

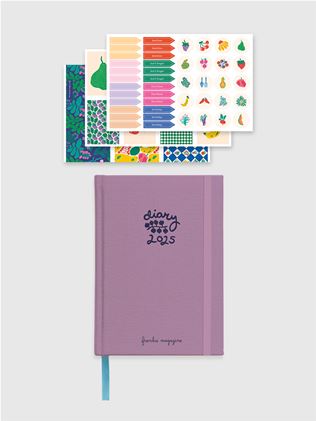

This story comes straight from the pages of issue 107. To get your mitts on a copy, swing past the frankie shop, subscribe or visit one of our lovely stockists.

.jpg&q=80&w=316&c=1&s=1)

.jpg&q=80&w=316&c=1&s=1)