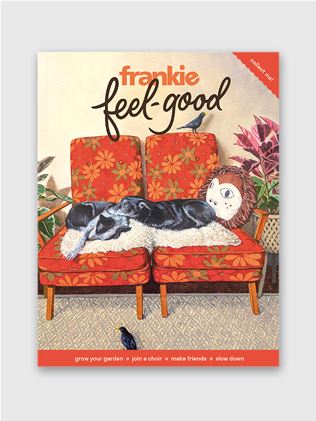

four iconic australian artists talk change, ageing, failure and creativity

Life advice from the elders.

Did you know UNiDAYS members can nab a 25 per cent discount on their frankie magazine subscriptions? Well, now you do. Check the bottom of the story for more deets.

Did you know UNiDAYS members can nab a 25 per cent discount on their frankie magazine subscriptions? Well, now you do. Check the bottom of the story for more deets.

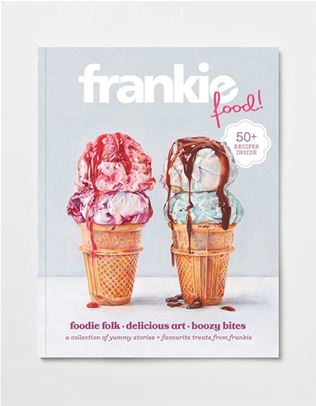

With support from the folks at UNiDays, we're revisiting some of our favourite stories from past issues. In this feature from frankie 52, first published in February 2013, writer Georgia Frances King meets four great Australian artists to find out what a lifetime of painting can teach you. Sadly, Robert Dickerson and Mirka Mora have since passed away, but their amazing works and wise words live on.

photo by Amanda Austin

ELISABETH CUMMINGS

What more do you still have to learn? I hope I’m still learning things. Some people latch on to things quicker, but it’s a slow process for me. It’s just the way the cookie crumbles – you can’t help your own temperament. I certainly don’t want to sit in one place and just repeat myself though, so there’s that desire to push beyond what I’m comfortable with. But whether I manage to do it is another thing! You can slip back into old habits easily. One has habitual ways of putting a brushstroke down. I try to be aware I don’t do it all the time, though.

What advantages does age bring? Painting always has its concerns and delights: it’s the whole business of doing something that feels like you’re extending yourself somehow. And that’s exciting. Growing old contains all sorts of good things. You don’t worry about preoccupations you had when you were younger. But physically I don’t have the energy I used to. I also have bad ankles, but I had one fixed up, which has helped a lot. Otherwise I feel pretty good.

How has the art world changed over the decades? I was brought up in Brisbane, but came to a Sydney art school in the 1950s. There were a lot of things happening in Europe and America at the time we were ignorant of – I had to find out about them later. My parents were very positive for that era, which was very rare. Artists are still a little marginalised, but not as much as they were in the ’50s. I’ve lived through many changes and have an open mind to a large extent, but the changes have been enormous. The art scene is baffling to me mostly.

How often do you paint now? I have to grab the days I can for painting and the other things in life like friends, my son and my grandkids. But when I have a good stretch of time I try to be reasonably disciplined, starting early and working through the day. (I've not often painted at night as I don’t like painting with artificial light.) It’s very valuable to have a continuous time to work – that’s the only way you’re going to have anything happen.

How do you make the time you paint count? Oh, I dilly dally. I dilly dally, then potter, then start… You can think there’s not much time left, but one does what one can. Although time is precious and one should feel the urgency of it, you can still do some dilly dallying!

Who or what do you turn to on uninspiring days? Oh, I don’t believe in inspiration! I think the only way is to keep working. And if you’re working then something might happen, even if a lot of it’s not marvellously good. Things unfold through the painting itself. And it’s exciting to be in that space when something new is happening.

What does creativity mean to you? Creativity means starting a painting and seeing what happens. It’s always a new adventure. everyone has creativity in some form or another. I love looking at children and seeing what they can do naturally. The analytical mind hasn’t clicked in yet. I’d love to get back to that childlike state of being without the filter of the rational mind. That’s very hard to cast off. But I would love to. At the times when I’m painting and things flow, you just touch that a little bit. And that’s the best.

What do you look back on and feel the proudest about? Oh goodness, I haven’t thought of being proud! Maybe just keeping on going – I suppose that’s something to be glad about. I’m just grateful really, more than proud. I'm still as excited about painting as I ever was. It’s still very fascinating. I love the challenge of it.

photo by Amanda Austin

ROBERT DICKERSON

When did you first become interested in art? I started painting during the war. I was up on an island in the Pacific after it ended and had nothing to do. I found a book of [post-impressionist artist] Gauguin’s paintings of the Pacific and thought, “If Gauguin can do it, I can do it, too.” So I used the old tent canvases and leftover camouflage paint and painted the Indonesian kids. They liked them and used to give me coconuts in exchange.

Has painting become easier with experience? To paint a good painting is a pretty rare thing to do. I love it. I’m quite excited by a good painting. I know exactly when a painting is good now. If you paint a dud one then you can sit there and make it into a good one – I just paint another picture on top of it. there are probably about four paintings under each one.

What do you think now looking back on your early works? I painted on cardboard and used to destroy most of them in the early period. There are only a few of them around now. I was once living in a little house with floorboards, and whenever I got a bit fed up with a picture I nailed the piece of cardboard with the painting on it to the floor. Anything I was happy with, I’d keep; anything I wasn’t happy with, I’d nail. They could have been good paintings when I look back at it, but I don’t really regret it.

How was your art perceived back when you were younger? When I was painting in the ’40s and ’50s, people didn’t have much respect for artists, that’s for sure. But I didn’t care. if I don’t like a painting when it’s finished I don’t care, so when people criticise it I still don’t care. You’ve got to make your own decisions about what a painting looks like.

How has your perception changed as the world has changed? I think it’s a very exciting time. Australia is different to what it was when I was a boy. There were only one million people in Sydney and no refugees: now it’s a completely different country with all sorts of people from everywhere. It’s liberty! It gives me a great escape to paint people. I like painting old ladies. They seem to be able to survive better than anybody. They’re tougher.

Do you consider yourself a tough person, too? Well, I’m still alive! That’s about the most of it! I hope to go a little bit longer. You’ve just got to want to do something. You’ve got to have ambition. I want to paint a really good painting all the time, and now I’ve got the time to do it in. I’m optimistic about anything – I like going to the races, too, and I like being optimistic about the horses.

How have your painting habits changed with age? I still paint every day. I used to paint all night when I was younger – I could still do that quite easily! Not a bad idea, actually… it’s very hard to go to bed and sleep through like I used to. But I'm still in good health. I can still walk rather well and do all sorts of things like swim and lift weights. If you keep exercising until the mind goes, then you’re OK. Once you fall into a slump then you’re a dead pickle.

What have you done to keep motivated over the decades? It’s not that complicated. It’s about how lazy you are. If you want to paint, you’ll do it. I always just painted because I wanted to. That’s my workout. The only advice I can give is to do your painting. And don’t worry about what other people say. You don’t take notice of people. You need to take notice of yourself.

photo by Hilary Walker

MIRKA MORA

What does art mean to you? It’s your soul. And you can’t work with people who don’t have a soul. Your art is your art – never dilute yourself. Nobody is allowed to tell you how to paint. Sometimes I try to tell myself what to do, but it never works! Because it’s not art if you decide to do something. Art is free, but of course you have to be alert to catch it when it comes onto the canvas. I don’t choose the ideas, they choose me. I don’t wait for them. They come without my permission.

Do you have to study to be an artist? I’m a self-taught person, so I don’t believe in rules. I lived in Paris and couldn’t go to school because there was the war and I was Jewish. But I'm lucky in a way that I didn’t go, because now I don’t have to obey the rules. While I'm alive, I have to understand what happened. I have to understand the concentration camps. But you can’t. I was in a concentration camp – I still hear the sound of the soldiers’ motorbike in my ears. A war is a war. You have people who are wonderful and save you, and you have people who are awful and don’t do a thing. But there are good people.

What has become easier as you’ve aged? I find life goes very quickly – I never see it! People suffer being old, but I think it’s fabulous. It’s like a new adolescence, and I missed out on mine because of the war. I jump like a kangaroo and fly around my house! I work sometimes to the limit, till I can’t move! I don’t wear glasses because they make me look stupid – I have a magnifying glass on a chain instead. But it doesn’t affect my work. That is the magic, because I can still see the slightest tonal mistake, even if it’s not bigger than half a millimetre. The optometrists don’t know what to do with me!

How was the Australian art scene different to Europe’s when you came here in 1951? Painters were starving because society was not sophisticated and educated enough. The National Gallery didn’t exist then. And galleries are very important to educate people. People respect art, but are suspicious of artists. But they’re more educated today. I never want to leave Melbourne. I was born in Paris – I don’t need to be there anymore.

How has your perspective of the world changed? It’s exactly the same. I haven’t grown up, but I am no fool. I'm a bit embarrassed to say this, but I don’t want to go into the real world. I threw away my digital camera as I thought it was frigid. I don’t participate in the internet, but I know it’s marvellous. Technology may save us, but why do we want to be saved?

What are you still trying to achieve? There is no present and there is no past. It’s just a kind of dream you live in. The perfect piece doesn’t exist. You cannot do it. I’m just learning. Life is about learning. And so is painting. If I wasn’t learning anything, I wouldn’t work. I just have to keep discovering. Picasso said that he doesn’t decide, he finds. The idea has to find you. If not, it’s not art. It’s something else. Art is more and more of a mysterious thing, but it’s still elusive to me.

Is there anything you would do differently if you could? A failure is always a success in my book. I'd never change, because I do what I want to do. The secret in life is to find beautiful people and surround yourself with them. I am a bee in disguise and my friends are flowers! I am still a rebel. And I still have a lot to learn.

Photo by Tom Sheffield

JOHN OLSEN

How has your relationship with your art shifted over the years? Our lives are many islands. The difference now is I have a better overview of things. For the Archibald Prize I won in 2005, I painted myself in profile looking both ways. This referred to Janus, the Roman god of entrances and exits. Being older certainly can cause apprehension, as I see the horizon getting closer, but we also have the advantage of so many memories of things we have done. As the Greek philosopher Epicurus said, being able to use memory creatively is much more profound than physical.

What are you still striving to create? I don’t believe in newness for newness’ sake, that’s one thing. During the Renaissance, the criteria wasn’t newness: the criteria was how to express something hugely complex. It comes down to consistent studio practice. Playing in a relaxed way allows the mind to circulate because you’re not concerned with failure. So many people can’t work freely because they don’t know how to play. There are so many people who go to work each day and hate what they’re doing. What they haven’t grasped is that life is a short holiday from eternity.

How do you keep motivated to paint every day? I’ll put it this way: I have a new studio, and it’s attached to my bedroom. Now that might seem such a simple thing, but it’s very important because I’ve got a notion I ought to keep the studio warm. It’s about being in the engine room of art.

What about your practice has become harder growing older? I am frustrated with my physical limitations: I’ve got to use a walking stick and it’s very hard for me to accept that. There is a youthful vitality I don’t have anymore, either. There was an enormous painting called Spanish Encounter I once painted overnight. I was going out with this lovely girl; it was Saturday night and she couldn’t go out. So I just picked up the brushes and it happened: a representation of frustration and entanglement, or non-entanglement in this case! I would never do that now, the sheer cheek and audacity of it!

How were artists perceived in your younger years? We were an underclass. The great thing about it was you had to do it because you loved it. There were no grants, there was nothing. Pictures by Sidney Nolan nobody wanted are now going for $3.5 million, and I still think they’re too cheap. And it’s not to be forgotten that Australia was very enclosed then. It was the tyranny of distance. The population when I was born was only 2.5 million. We’ve come so far and it’s such a great achievement.

What did your parents think of what you did? There were no pictures at all in my parents’ home. None at all. We’d never even been to an art gallery. So when I announced that I was leaving my job and this was going to be my life, my mother said, “What will the neighbours say?” And my father put his arm over my shoulders and said, “Y’know, son? You’re going to be mixing with some very strange people.” And by God, he was right.

What have you discovered about failure? A bad day’s painting or a failure doesn’t concern me, because in a failure you can learn something. You shouldn’t get upset about it. Go pour yourself a glass of wine at the end of the day, because there is tomorrow.

Is there anything you wish you’d learned earlier? Yes, all of the things I’ve just told you!

Do you think you’ll ever stop painting? An artist never retires. It’s the greatest thing. He doesn’t put the brushes down and play golf. It means continuity, struggling with new meanings and new ways of looking at things. It’s a marvellous thing.

Thanks to the kind types at UNiDAYS, uni students can nab 25 per cent off their frankie subscriptions. Just click here, then register or log in using your UNiDAYS member details. Easy as!

.jpg&q=80&w=316&c=1&s=1)

.jpg&q=80&w=316&c=1&s=1)